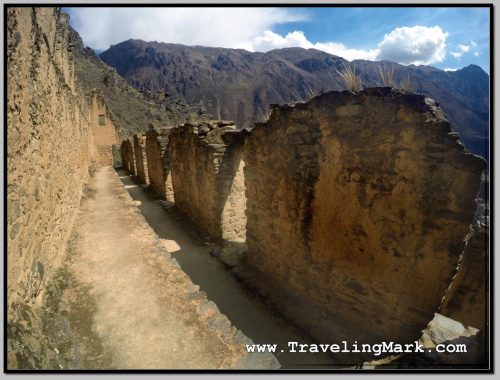

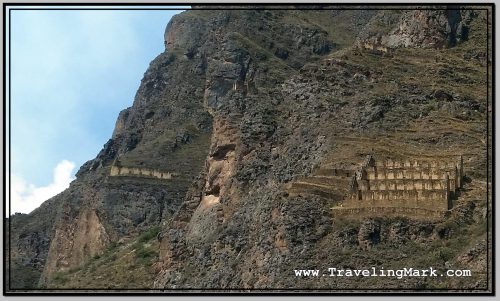

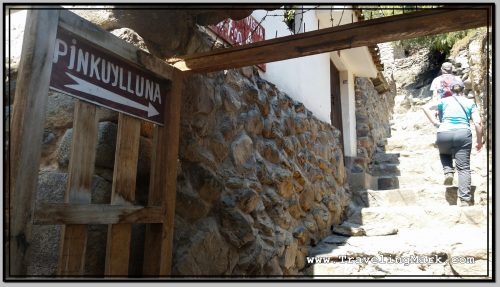

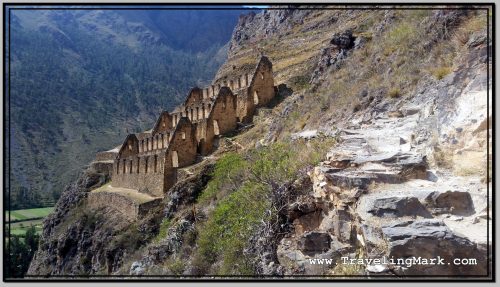

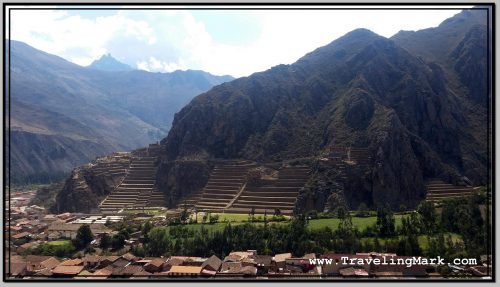

Having arrived from Cusco, gotten a room, explored the ruins on the Pinkuylluna Mountain, and filled my belly with fried trout, I felt like I’ve seized the day pretty well, but whereas I still had an hour until the sunset, I decide to get off the beaten path in Ollantaytambo and explored its least visited areas.

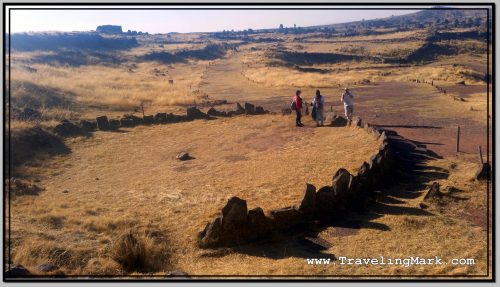

I found out while messing around the town’s main square of Plaza de Armas that just outside of the town boundaries on Ollantaytambo’s south-east side, can be encountered the ruins of an ancient Inca bridge, and that near said bridge lay also the ruins of an Inca pyramid. I hit it off to check those out.

Getting to the Inca Bridge

I started the walk from the south-eastern corner of Plaza de Armas and followed the road due east, passing the small market with incredibly overpriced fruits (Peru is expensive to begin with, but it’s even worse as you get closer to Machu Picchu – Ollantaytambo was second only to Aguas Calientes, which is at the foot of Machu Picchu), and onward down the road, until I reached a T intersection. There I turned left and after a few meters immediately right to carry on due east.

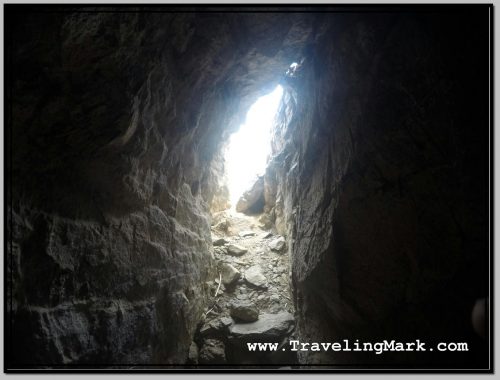

On that road I passed Inka Paradise hotel and some kind of a school, after which there was a narrow pedestrian dirt road through a field. That road leads to the bridge. Except at the end of it, there’s a cliff that needs to be descended so if you didn’t take the stroll in your hiking boots, you will only get to enjoy the bird’s eye view of the bridge, and no pyramid.

An alternative is to go around town by following the road back to Cusco, but that road is narrow with no sidewalks to safely walk on and the drivers don’t pay much respect to pedestrians.

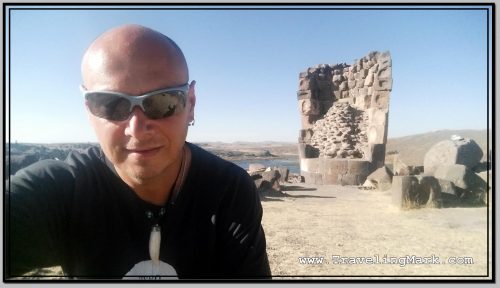

Inca Bridge

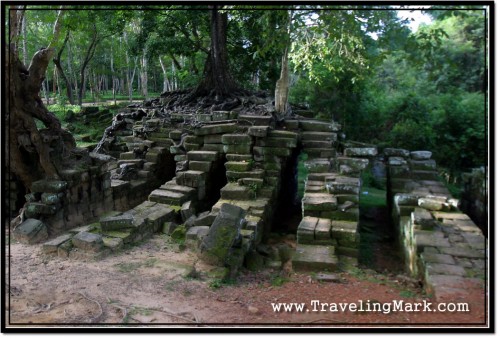

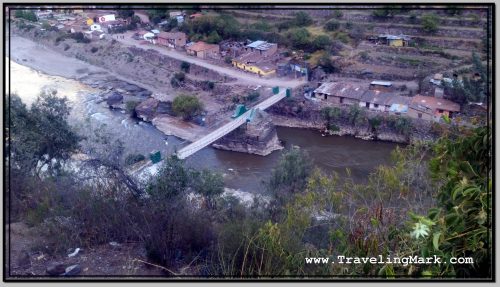

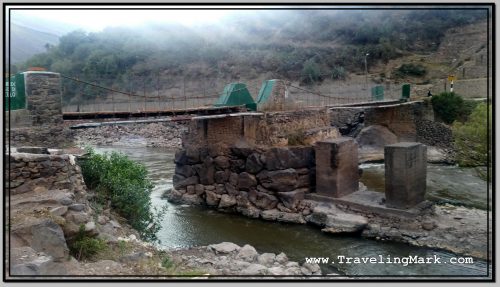

There isn’t a whole lot left of the ancient Inca Bridge. Just the support column erected in the middle of the Vilcanota river still holds the original stones used for its constructions. Nowadays, a newly built suspension bridge connects that banks of the river, still utilizing the remnants of the old Inca structure.

Along the Ollantaytambo side of the river there are railway tracks leading to Aguas Calientes, but no road so tourists don’t have the means to get themselves near Machu Picchu, and are stuck having to use the train for which they are charged more than 100 times the cost of the locals. It is a major and blatantly deliberate rip off which I refused to support.

While I was at the bridge, a train with ripped off tourists returning from Machu Picchu back into Cusco passed bay.

Ollantaytambo Inca Pyramid

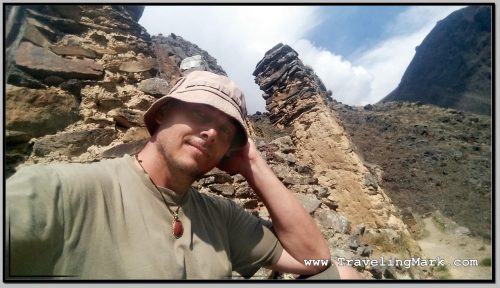

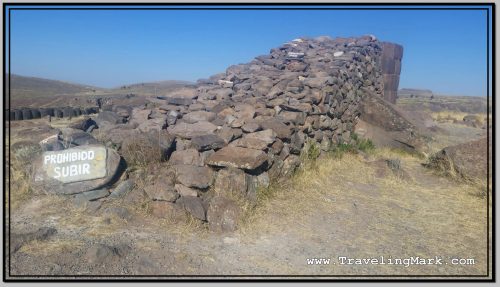

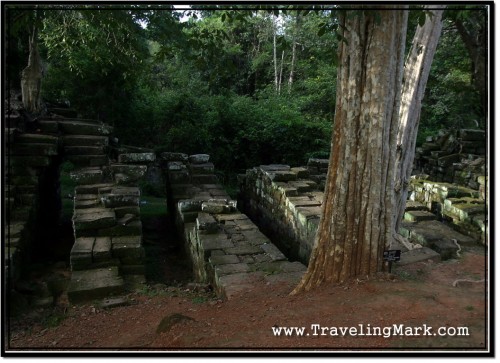

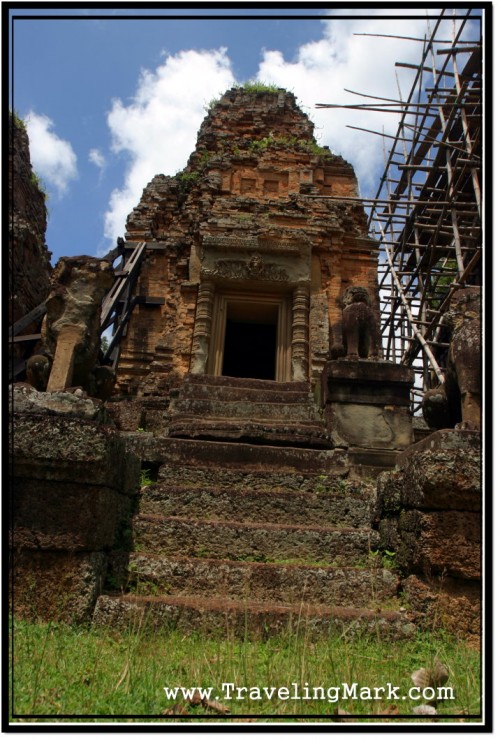

On the other side of the tracks from the bridge is the pyramid. It is a cascading stone structure build into the slope. I didn’t come across any reasonable kind of backinfo about the pyramid, except that it’s there, near the bridge next to the tracks.

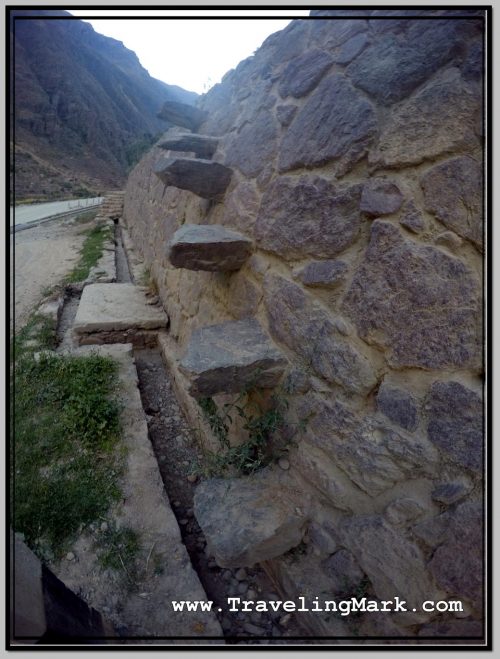

Te pyramid had a set of protruding stones built into the outer wall, to serve as steps for ascend. Despite dodgy looking purpose, those steps are solid and absolutely safe to walk on, having withstood the test of time – centuries after being built, they are still there in their original form after affording countless people the way up on the pyramid.

Because the way I came to the area involved a descend down a very steep cliff including a near 2 meter jump, going the same way back was not an option, so I walked around town down the paved road from Cusco.

The vast majority of people who come to Ollantaytambo will only visit the fortress – having shelled out some $43 for the entrance to the archeological sites within the Sacred Valley of the Incas. They come on buses as part of organized tours which only take them to the fortress and nowhere else. So whereas the fortress is overrun with hundreds of tourists every single day, the nearby Pinkuylluna Mountain, which is free to visit receives very few visitors, but when it comes to the Inca Bridge and the Pyramid on the opposite side of the river, your chances of spotting another tourist around them are next to none.